Halil Akdeniz | Selected Bio Texts

A New Model For Shaping In Painting

Italian writer-aesthetician Umberto Eco’s thoughts on how communication between the work of art and the audience is liable to develop may basically be grounded on on his statement conserning how it should be avoided that a single meaning be imposed on the reader (the audience). According to Eco, the work of art should make it possible that the audience’s free participation be a preliminary condition and that a cooperative atmosphere be created whereby the audience can infer things from the work that the latter does not say as such but does imply. Developed around the thesis that the work of art is open to interpretation, these thoughts openly inform us that art works are lazy pieces of machineries that need to be set in motion by the audience. For the spectator’s entering a process of reading, understanding and interpreting, using as their point of departure elements that are part of the work, will render possible an ideal relationship that enables the consumption of the work.

The process, which we’ve been mentioning in an Eco-based framework, and which envisages the will to understand-interpret the work, is actually part of the work-oriented critical system in line with principles of semiotics and semantics.

Halil Akdeniz bases his painting on the historical environment and cultural inputs gathered after long-term research and experimentation; his art enables the audience to communicate with signs, writings or symbols stemming from Anatolian Civilizations, and sets a positive example for this type of task, which involves the understanding and interpretation of the work of art in terms of the signs it comprises and the meanings it calls to mind. To point out from the outset; this task need not perfectly dovetail with the artist’s thoughts or justifications for composing his work. The essential is that that the audience be able to produce, conceive and proliferate hypotheses regarding the work. Because in this respect Akdeniz’s work is not easily consumed or understood, and because it is not a style of painting that incorporates commonplace elements, it is a type of painting that from the outset discourages the audience’s mobility. However, the clues the artist provides for the audience, also on a plane that is proposed by the thematic tendency, are of an order that can give rise to many associations and interpretations in an audience that is willing and insistent. In this article, in which we can describe Halil Akdeniz as a brand new model for shaping in painting, we have attempted to understand the artist’s approach based on the visual elements it comprises, and to clarify our findings in free-style (spot) readings.

I.

Halil Akdeniz is an artist who is engaged in painting on canvas in the traditional sense of the term, and in the problems related to the canvas surface. What saves him from this narrow scope, what renders him different from the traditional attitude is the way he is inclined to perceive the canvas surface and his ability to use it as he wishes. In fact, he is the first artist of Turkish Painting to have experimented with fundamental physical positions such as superimposed canvases or unequal diptychs, and to have adapted these to the problematics of his paintings. This situation of developing for his own sake the aforementioned types of geometric structural characteristics while at the same time equating to such a degree the plastic expression with the theme he addresses has actually placed Akdeniz in a special position from the very outset.

II.

It is noteworthy that when the artist went back to Germany, where he had completed his specialized training, he started showing an affinity toward abstract-geometric interests. Actually this period encompasses a series of beginning paintings that are variations on the problem of surface effect. This period is actually that in which he becomes acquainted with the tools that the painting necessitates for its own sake and in which the surface calls to mind the possible solutions. For the experience gained at this time has easily provided the foundation necessary for a plastic structuring because it corresponds to a topical problem the artist encountered in Izmir where he lived in 1977-78.

The “Pollution in the Gulf”, a phenomenon which has made itself felt as an urgent matter, has become a prominent issue to which Akdeniz has not remained indifferent and out of which he has gradually made his main theme after having carried his first reckonings onto an artistic plane. Rather than mimicking the phenomenon through its explicit signs, he gravitated toward serial paintings that were to help develop out of this phenomenon a new surface-color and its formal relationships. Beyond determining the socioecological importance and gravity of the situation, the artist has aesthetised the status the problem had acquired at the time through scientific inputs and signs, and has treated the subject using spare and direct expressions. Within this context, each of his paintings in the series “Visual Notes on the Pollution in the Gulf” can be considered as a “situation assessment”, and in this sense they, at the same time, have become “document paintings” that explore the development of an ecological phenomenon.

III.

The fact that Akdeniz started living in Ankara after 1987 also points to the beginning of a period that was to add new perspectives to his view of the environment. During this process, the artist engaged in a historical and sociological study that first included Ancient Greek Civilizations in Western Anatolia, and immediately afterwards also encompassed the Hittite Civilization, which is also one of the past cultural riches of Central Anatolia. Observations as to the topical, which he has been bringing to bear since the beginning, were brought together on the same painting surface with inputs related to the past via certain selected signlike elements. This situation lead to the clash of the signs created (perhaps) purposefully by the artist, and the meanings they contain.

Actually, all the elements that convey the theme of the “Pollution in the Gulf” at the level of a special plastic interpretation have also conveyed a pictorial approach to painting that develops and becomes varied by transforming into a language (discourse) that becomes original within the form-meaning relationship. In the same way, in his more recent paintings, forms that have been determined so as to correspond to the string of historical (archaeological) and cultural values also maintain their usual versatile, stimulating, and meaningful functions.

One must particularly point out that many meaningful, spare and effective signs have a motivating power to compell the audience to reconceive the work on a metalinguistic plane. In this regard, during the genesis of Akdeniz’s paintings, an important cause lies behind the purification of the complexity of lign and color, and the meticulousness in the choice of elements.

IV. Another observation is that the surface, which functions as the background in Akdeniz’s paintings, is a symbol surface that is the reflection of the artist’s archaeological interests. Indeed, the surface’s textural character is the first stage; stage during which the thought which the painting is completely based on is rendered visual. And from then on this texture in Akdeniz’s paintings becomes a distinguishing identity, a signature.

V.

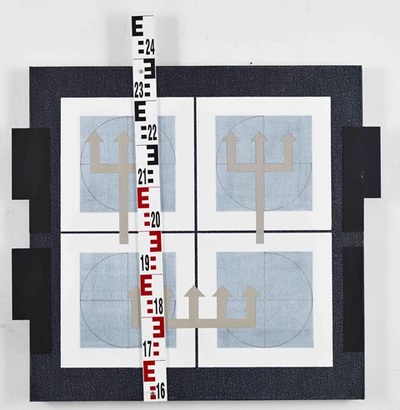

The series and individual paintings “Anatolian Civilizations - Visual Notes” basically are inclined toward “quotation”. The choice of symbols that are to make possible the communication of information regarding the historical period the artist draws on in his paintings, is based on this quotation method. By attributing new meaning to a form quoted from the historical and social context of the surface of a same painting, the form can acquire a new existence within a different context. (Deconstruction and Reconstruction) Or, the same form (symbol) confronts a set of new forms regarding the topical, far beyond the origin and experience from which it has been quoted. When a relationship is established between a writing or sign taken from tombs and a measuring instrument (such as a triangle or range pole), what emerges is a situation which could be explained through the pattern of relationships between cultures and environments.

VI.

Halil Akdeniz attaches importance to the image, and more and more to the forming of a contemporary visual language. Therefore he makes use to a great extent of ancillary elements that target the image. Akdeniz acts within an exploratory system aimed at the meaning (thought) he wants to communicate via the chosen object or image (form). The effort to develop a meaning whose effect would be to stimulate thought gradually necessitates a structuring that responds to the requirements of plastic concerns such as discipline, balance and harmony. Consequently the structure manifested by Akdeniz’s art is one that is enduring, conceals signs of enthusiasm, and cannot be easily analysed. All in all it would not be mistaken to assess Akdeniz on a plane parallel to the interests of Conceptual Art in terms of the way he problematizes the image and the way he treats it or experiments with the possibilities of visual expression addressing the image. At this point, it is also possible to describe the artist as a painter who bases his art on the presentation of thought through those tools and working gear that would best render it visual, without contenting himself with its existence in the conceptual dimension. For without an analysis to render it visual within an artistic context, pure thought is bound to remain singular and temporary. By turning a radical gaze directed at the society in which he lives, a gaze that is aware of the abovementioned fact, Akdeniz knows how to capture the intellectual and practical results that are to form the inner dynamics of his art.

1 Umberto Eco, Alımlama Göstergebilimi (The Semiotics of Reception), Translated from French into Turkish by Sema Rifat, Dülzem Pub. 1991, Istanbul, pp. 8-10.

2 See : “Halil Akdeniz’le Görüşme” (Interview with Halil Akdeniz), Yeni Boyut, Vol. 10, Feb. 1993, pp. 29-32

Mümtaz Sağlam

Italian writer-aesthetician Umberto Eco’s thoughts on how communication between the work of art and the audience is liable to develop may basically be grounded on on his statement conserning how it should be avoided that a single meaning be imposed on the reader (the audience). According to Eco, the work of art should make it possible that the audience’s free participation be a preliminary condition and that a cooperative atmosphere be created whereby the audience can infer things from the work that the latter does not say as such but does imply. Developed around the thesis that the work of art is open to interpretation, these thoughts openly inform us that art works are lazy pieces of machineries that need to be set in motion by the audience. For the spectator’s entering a process of reading, understanding and interpreting, using as their point of departure elements that are part of the work, will render possible an ideal relationship that enables the consumption of the work.

The process, which we’ve been mentioning in an Eco-based framework, and which envisages the will to understand-interpret the work, is actually part of the work-oriented critical system in line with principles of semiotics and semantics.

Halil Akdeniz bases his painting on the historical environment and cultural inputs gathered after long-term research and experimentation; his art enables the audience to communicate with signs, writings or symbols stemming from Anatolian Civilizations, and sets a positive example for this type of task, which involves the understanding and interpretation of the work of art in terms of the signs it comprises and the meanings it calls to mind. To point out from the outset; this task need not perfectly dovetail with the artist’s thoughts or justifications for composing his work. The essential is that that the audience be able to produce, conceive and proliferate hypotheses regarding the work. Because in this respect Akdeniz’s work is not easily consumed or understood, and because it is not a style of painting that incorporates commonplace elements, it is a type of painting that from the outset discourages the audience’s mobility. However, the clues the artist provides for the audience, also on a plane that is proposed by the thematic tendency, are of an order that can give rise to many associations and interpretations in an audience that is willing and insistent. In this article, in which we can describe Halil Akdeniz as a brand new model for shaping in painting, we have attempted to understand the artist’s approach based on the visual elements it comprises, and to clarify our findings in free-style (spot) readings.

I.

Halil Akdeniz is an artist who is engaged in painting on canvas in the traditional sense of the term, and in the problems related to the canvas surface. What saves him from this narrow scope, what renders him different from the traditional attitude is the way he is inclined to perceive the canvas surface and his ability to use it as he wishes. In fact, he is the first artist of Turkish Painting to have experimented with fundamental physical positions such as superimposed canvases or unequal diptychs, and to have adapted these to the problematics of his paintings. This situation of developing for his own sake the aforementioned types of geometric structural characteristics while at the same time equating to such a degree the plastic expression with the theme he addresses has actually placed Akdeniz in a special position from the very outset.

II.

It is noteworthy that when the artist went back to Germany, where he had completed his specialized training, he started showing an affinity toward abstract-geometric interests. Actually this period encompasses a series of beginning paintings that are variations on the problem of surface effect. This period is actually that in which he becomes acquainted with the tools that the painting necessitates for its own sake and in which the surface calls to mind the possible solutions. For the experience gained at this time has easily provided the foundation necessary for a plastic structuring because it corresponds to a topical problem the artist encountered in Izmir where he lived in 1977-78.

The “Pollution in the Gulf”, a phenomenon which has made itself felt as an urgent matter, has become a prominent issue to which Akdeniz has not remained indifferent and out of which he has gradually made his main theme after having carried his first reckonings onto an artistic plane. Rather than mimicking the phenomenon through its explicit signs, he gravitated toward serial paintings that were to help develop out of this phenomenon a new surface-color and its formal relationships. Beyond determining the socioecological importance and gravity of the situation, the artist has aesthetised the status the problem had acquired at the time through scientific inputs and signs, and has treated the subject using spare and direct expressions. Within this context, each of his paintings in the series “Visual Notes on the Pollution in the Gulf” can be considered as a “situation assessment”, and in this sense they, at the same time, have become “document paintings” that explore the development of an ecological phenomenon.

III.

The fact that Akdeniz started living in Ankara after 1987 also points to the beginning of a period that was to add new perspectives to his view of the environment. During this process, the artist engaged in a historical and sociological study that first included Ancient Greek Civilizations in Western Anatolia, and immediately afterwards also encompassed the Hittite Civilization, which is also one of the past cultural riches of Central Anatolia. Observations as to the topical, which he has been bringing to bear since the beginning, were brought together on the same painting surface with inputs related to the past via certain selected signlike elements. This situation lead to the clash of the signs created (perhaps) purposefully by the artist, and the meanings they contain.

Actually, all the elements that convey the theme of the “Pollution in the Gulf” at the level of a special plastic interpretation have also conveyed a pictorial approach to painting that develops and becomes varied by transforming into a language (discourse) that becomes original within the form-meaning relationship. In the same way, in his more recent paintings, forms that have been determined so as to correspond to the string of historical (archaeological) and cultural values also maintain their usual versatile, stimulating, and meaningful functions.

One must particularly point out that many meaningful, spare and effective signs have a motivating power to compell the audience to reconceive the work on a metalinguistic plane. In this regard, during the genesis of Akdeniz’s paintings, an important cause lies behind the purification of the complexity of lign and color, and the meticulousness in the choice of elements.

IV. Another observation is that the surface, which functions as the background in Akdeniz’s paintings, is a symbol surface that is the reflection of the artist’s archaeological interests. Indeed, the surface’s textural character is the first stage; stage during which the thought which the painting is completely based on is rendered visual. And from then on this texture in Akdeniz’s paintings becomes a distinguishing identity, a signature.

V.

The series and individual paintings “Anatolian Civilizations - Visual Notes” basically are inclined toward “quotation”. The choice of symbols that are to make possible the communication of information regarding the historical period the artist draws on in his paintings, is based on this quotation method. By attributing new meaning to a form quoted from the historical and social context of the surface of a same painting, the form can acquire a new existence within a different context. (Deconstruction and Reconstruction) Or, the same form (symbol) confronts a set of new forms regarding the topical, far beyond the origin and experience from which it has been quoted. When a relationship is established between a writing or sign taken from tombs and a measuring instrument (such as a triangle or range pole), what emerges is a situation which could be explained through the pattern of relationships between cultures and environments.

VI.

Halil Akdeniz attaches importance to the image, and more and more to the forming of a contemporary visual language. Therefore he makes use to a great extent of ancillary elements that target the image. Akdeniz acts within an exploratory system aimed at the meaning (thought) he wants to communicate via the chosen object or image (form). The effort to develop a meaning whose effect would be to stimulate thought gradually necessitates a structuring that responds to the requirements of plastic concerns such as discipline, balance and harmony. Consequently the structure manifested by Akdeniz’s art is one that is enduring, conceals signs of enthusiasm, and cannot be easily analysed. All in all it would not be mistaken to assess Akdeniz on a plane parallel to the interests of Conceptual Art in terms of the way he problematizes the image and the way he treats it or experiments with the possibilities of visual expression addressing the image. At this point, it is also possible to describe the artist as a painter who bases his art on the presentation of thought through those tools and working gear that would best render it visual, without contenting himself with its existence in the conceptual dimension. For without an analysis to render it visual within an artistic context, pure thought is bound to remain singular and temporary. By turning a radical gaze directed at the society in which he lives, a gaze that is aware of the abovementioned fact, Akdeniz knows how to capture the intellectual and practical results that are to form the inner dynamics of his art.

1 Umberto Eco, Alımlama Göstergebilimi (The Semiotics of Reception), Translated from French into Turkish by Sema Rifat, Dülzem Pub. 1991, Istanbul, pp. 8-10.

2 See : “Halil Akdeniz’le Görüşme” (Interview with Halil Akdeniz), Yeni Boyut, Vol. 10, Feb. 1993, pp. 29-32

Mümtaz Sağlam